History off of the paper

History in the physical and visual

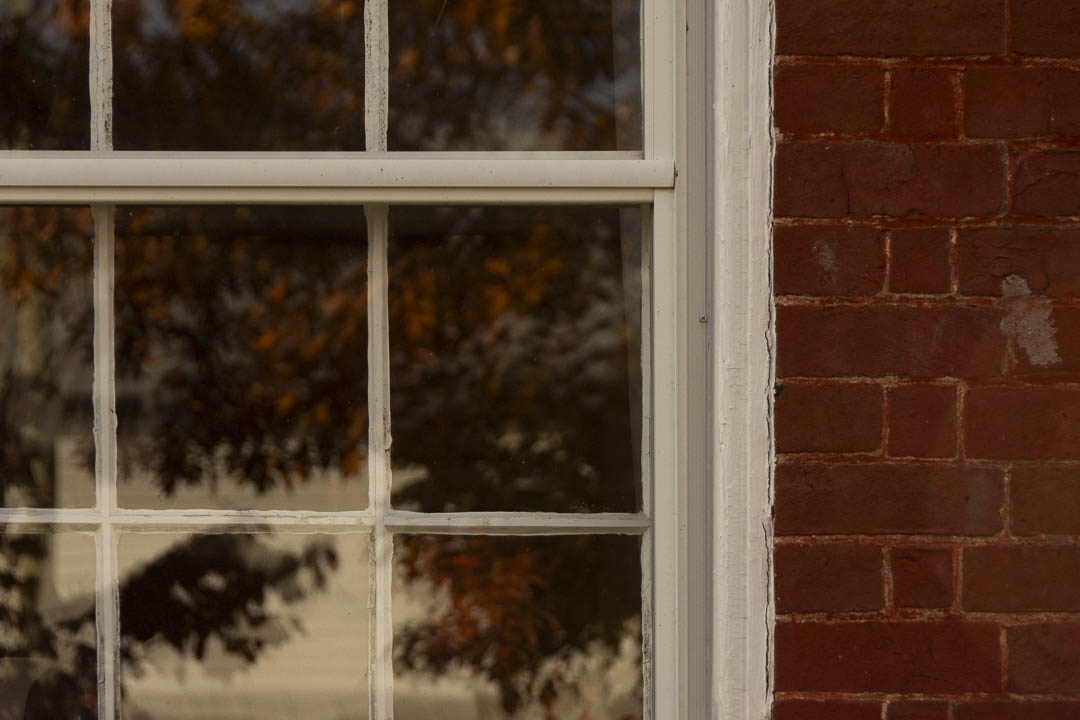

In an earlier post, I talked about my interview with a client about why old homes are worth saving, and he took me on a tour to share the history while pointing out details. In our interview, our client highlighted the importance of restoring old buildings because “[they] are tangible elements of history,” and emphasized that seeing history in the physical and visual is much more enjoyable than reading it on paper.

He was absolutely right. During the tour, I found myself getting more and more excited about history, especially of historic buildings. Seeing history in-person instead of just reading text connected me to the stories much more than I had before.

All that said, it is ironic that I’m writing about how seeing history in physical form connected me to it much more than reading about the history. To combat the irony just a bit, below are photos with tidbits from our interview and tour.

Photo details of our client’s house

After the Revolutionary War, some Hessian mercenaries (recruited from Germany to fill the British ranks) were left on the continent. They brought some German design elements/heritage with them which blended over time with emerging American preferences. You can see this in the hand carvings and style of the mantles (6 were fireplaces in the house, some restored now).

Downstairs by the kitchen there’s a china cabinet that the current owners painted dark green in keeping with the old color scheme. But if you look inside, you can see the old paint which is a brighter green – more of a lime green. This color was popular among German settlers, including Mennonites, Lutherans, and others who included that color as they moved down into the Shenandoah area from Central Pennsylvania.

Remnants of the lime-green paint are also on this door.

Round brick columns, typical to the time period.

Throughout the years, larger rooms were sectioned off into smaller ones, like the Great Room. They can tell where the Great Room was because the boards are perfectly aligned between a couple existing rooms. Uniform board lengths with no cuts was a symbol of status, which would have been put in the Great Room.

The milk paint on the detailing in this room is mulberry colored. This seems to be a popular color of milk paint for the time.

There isn’t written history of this, but it’s been passed down orally that a cannonball broke this upstairs window.

Builders numbered the attic timber beams with carved roman numerals so they would know the order to put them in when they hauled them to the house.

Wooden pegs in the attic to secure the beams together.

A hanging stepped flue in the attic – a very unique element.

Just for fun. As a photographer, I always love when furry friends come to say hello in my shoots.

Finally, here are a few more pictures from my photoshoot of our client’s porch after the historical porch renovation.